August 1, 2024, 6:55 am | Read time: 5 minutes

In the animal world, there are true masters of deceleration. Many people might first think of the snail, which slithers through the garden bed at a snail’s pace, or the well-known sloth. But there are other animal species in water and on land that live a life in slow motion. PETBOOK presents the eight slowest animals in the world.

In a large-scale study in which they analyzed data from hundreds of animal species, scientists at Friedrich Schiller University in Jena came to the conclusion that very large animals are generally the slowest animals. The reason for this is that they would otherwise overheat, as they do not get rid of their body heat as quickly as small animals. If you think of herds of elephants moving at a leisurely pace in the African savanna, you can understand why. But there are also very small animals that don’t exactly lead a life in the fast lane.

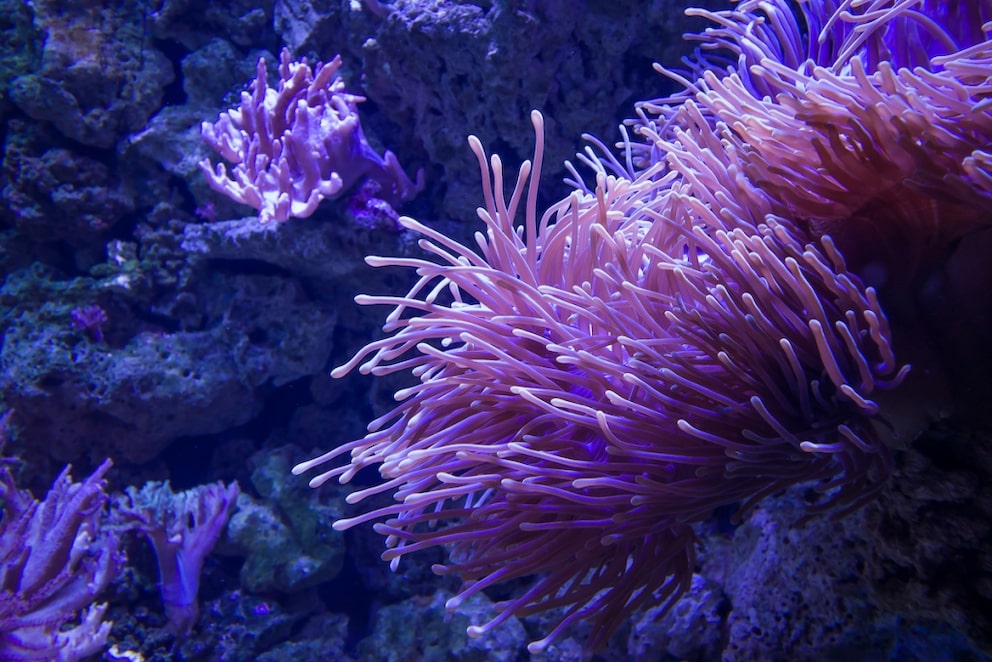

1. Sea Anemone (Actiniaria)

It belongs to the class of flower animals, lives on the seabed, and is slower than a snail. The sea anemone is a semi-sedentary animal. While a sessile animal is not able to move at all and does not change its location (such as mussels, sponges, and corals), the sea anemone moves around. Although it is capable of moving very slowly, it rarely does so. As a rule, it prefers to wait for its food in the form of a fish or crab passing by. This is more effective for them than moving only one centimeter (ca. 0.39 inches) per hour on their foot disc.

2. Banana Slug (Ariolimax)

The banana slug, which is widespread in North America, is a genus of large land-dwelling nudibranchs and is one of the slowest animals in the world. It got its name because of its often yellow coloration with brown spots. However, some specimens are also a greenish to brownish color. Depending on the species, they can grow up to 25 centimeters (9.8 inches) long when stretched out. The foot of the snail, which is the area where the body is flattened on the ventral side, is moved with the help of the mucus they produce. This allows them to move around 10 centimeters (3.9 inches) per hour. Fortunately, it does not necessarily have to go in search of a partner; although it is a hermaphrodite, it can also fertilize itself.

3. Starfish (Asteroidea)

Another aquatic slow mover is the starfish. When diving, it is usually seen sitting on corals or stones, but it actually moves around with its small feet. To do this, it attaches itself to the desired spot and drags its body behind it. On average, it moves one centimeter (0.39 inches) per minute, but it can also reach top speeds of five (1.96 inches) to eight centimeters (3.14 inches) per minute.

4. Seahorse (Hippocampus)

These small sea creatures are also very slow and swim at a speed of about 0.016 km/h (0.009 mph). To do this, the bony fish, which moves vertically, uses its back and pectoral fins; there is no tail fin. It uses its tail to anchor itself to seagrass, but also to other species.

5. Spotted Garden Snail (Cornu aspersum)

This snail moves through the Mediterranean region at a speed of around 0.048 km/h (0.029 mph), making it one of the slowest animals in the world. When making love, it presses its foot, on which it usually glides slowly, onto the foot of the other snail. It is also a hermaphrodite and has both male and female sexual organs. In England, it is often kept as a pet.

6. Three-Toed Sloth (Bradypus)

These animals, which are found in Central and South America, move at a speed of around 0.24 km/h (0.15 mph), which is about four meters (13 feet) per minute. They use their long arms and hooked, sharp claws to shimmy through the treetops like dream walkers. They are even slower on the ground, managing just 2.4 meters (7.8 feet) per minute. They recover from the “stress” by sleeping for around 16 hours a day.

7. Galápagos Giant Tortoise (Chelonoidis niger)

These giant tortoises move across the islands with their heavy shells at a speed of around 0.3 km/h (0.18 mph). The last representative of the species C. Abingdonii, “Lonesome George”, died at the age of 100 in Galapagos National Park after no more females of this species could be found.

Its smaller relative, the Gopher Tortoise, sometimes moves even more slowly, from 0.21 (0.13) to 0.48 km/h (0.29 mph).

Six facts worth knowing about the world’s largest turtle

Turtle sets a new diving record

The 9 Longest-Living Species in the World

8. West Indian Manatee (Trichechus)

Also known as manatees, these heavy animals (500 kg or 1102 lbs) bob in the water at a speed of around three (1.8) to five km/h (3.1 mph). They use their fluke (singular tail fin) and their forelimbs to steer. They live in both salt and fresh water in mangrove areas and lagoons. Manatees lead a very relaxed life, a feeding phase of up to eight hours is followed by a ten-hour resting phase.

Also interesting: 3 practically immortal animals

Conclusion: Slowness has nothing to do with laziness, but is simply a clever energy-saving concept for the slowest animals and their respective species. The sloth, for example, can survive on leaves that provide few nutrients. The koala, which only eats eucalyptus leaves, also lives in energy-saving mode and sleeps for around 20 hours a day.12